Part One: The Inheritance

Mission Hills in January looked like a photograph from a magazine about wealth. The kind of magazine that didn't acknowledge winter as an inconvenience, only as an aesthetic choice. Snow sat on lawns like it had been arranged there. Trees stood bare but dignified against a gray sky. The houses—mansions, really, though the people who lived in them would never use that word—were set back from the road behind walls and hedges and the particular kind of silence that money could buy.

Garrett Milligan parked his Civic on the street. It looked wrong here, like Comic Sans font in a legal document. Or any document, honestly. He sat for a moment with the engine off, watching his breath fog the windshield, remembering the phone call that had brought him here.

Margot's voice had that clipped efficiency she'd inherited from their mother. No preamble, or "how are you"—they'd long since stopped pretending to care about each other's lives. "Grandfather passed this morning. The funeral is Saturday, family only."

Am I family? Garrett had wanted to ask, but he'd been standing on the loading dock at Midwest Restaurant Supply, the smell of cardboard and diesel thick in the January air, and Dave the shift supervisor had been watching him with that look people got when anyone dared use their phone. So he'd just said "Okay" and waited for whatever came next.

What came next was a proposition.

"Grandfather's house needs to be cleared out," Margot had said. "The furniture, the books, his papers—everything. I'd like you to do it. Twenty-five dollars an hour, cash."

The arithmetic started firing through his head without him even trying. Twenty-five an hour, forty hours a week, for a month—maybe longer, if he was thorough. More money than he'd saved in the past two years of hauling fryer baskets and industrial dishwashers for men who'd stopped expecting anything better from their lives.

"Why me?" he'd asked.

"I'm sorry?"

"You could hire an estate company. Have professionals catalog everything, run an estate sale. You'd probably make money instead of spending it."

"Grandfather would have wanted it kept in the family."

That crisp edge in her voice. Garrett remembered it from childhood, from the times she'd told their parents he'd broken something or said something cruel. The lies had come easily to her then. They still did.

But he needed the money. He needed it badly enough to pretend he believed her.

Now he was here, sitting in his rusted Civic in a neighborhood where the cheapest house cost more than he'd earn in a lifetime, about to walk into a home he hadn't entered in over a decade. Since before. Since the summer they'd sent him away.

Garrett got out of the car.

The Milligan house sat at the end of a curving drive, limestone and leaded glass, three stories of old Kansas City money made solid. Garrett's shoes crunched on the salted walkway as he approached, the sound driving a stab of panic into his stomach. You’re allowed to be here. You’re not breaking any rules. No one is mad at you. You are allowed to exist.

The four sentences repeated in his head, a mantra taught to him by an old girlfriend. Daphne. Who had started off as his counselor, and finished with a polite request to never contact her again. Of course he respected her wishes. But he kept the mantra at the ready whenever it was needed.

He remembered standing in this circular drive at fifteen, waiting for his father's car. His grandfather had watched from an upstairs window. Hadn't waved. Hadn't come down to say goodbye. Just watched, like Garrett was a mildly interesting rerun of JAG.

Two weeks later, Garrett was in the Utah wilderness with thirty other "troubled" boys, learning what his family meant by correction.

The key was under a stone frog by the front door. Margot had told him where to find it, her voice suggesting this was a temporary security measure and not the way the key had lived for forty years. Some things about old money never changed. They didn't fear burglars. Burglars knew better than to steal from people who owned the police.

The door swung open on silent hinges. The smell hit him first: leather and wood polish and something stale underneath. Cigars, maybe. And age. The house smelled like a man who'd lived alone for too long, who'd stopped noticing the way his life had begun to decay around him.

Stepping inside, he allowed himself an appraising look upward.

The foyer was two stories tall, a staircase curving up to a landing where a window let in gray winter light. Portraits lined the walls. Milligans going back four generations, men in suits with hard eyes and women in pearls with harder smiles. Garrett found his father in the lineup—younger, thinner, but with that same expression of faint disappointment that had calcified into permanence by the time Garrett was old enough to recognize it.

Father had been dead for three years now. Heart attack at sixty-seven and a funeral attended by Kansas City’s finest. Garrett hadn't been invited.

He'd found out from a Google alert he'd set up years ago, a small act of self-torture he couldn't quite explain. He'd read the obituary in his apartment, alone, and waited to feel something. Grief. Relief. Rage.

Nothing came. He'd learned to keep the nothing close, to wrap it around himself like insulation. The nothing was safe. The nothing kept him from becoming someone he was afraid to meet.

He didn't look for his own portrait. He knew he wasn't there.

The main floor was a museum of a particular kind of life: sitting rooms with furniture no one sat in, a dining room with a table that could seat twenty, a library with books arranged by color rather than author. Garrett's grandmother had done that, back when she was alive and cared about things like the visual harmony of a bookshelf. She'd been dead for fifteen years. No one had rearranged them since.

Garrett moved through the rooms slowly, touching things. A crystal decanter, empty but still smelling faintly of bourbon. A silver letter opener shaped like a sword. A photograph of Margot's wedding, silver-framed, positioned on the mantle where visitors would see it. Margot actually managed to look pretty. Genuinely happy, even. Reed beside her with his politician's smile and his old-money jaw.

Garrett wasn't in that photograph either.

Something flickered in his chest—hot, quick, dangerous. He'd learned to recognize it the way you learned to recognize the first spark before a fire. Snuff it out. Don't let it catch. Don't let them see.

He'd never been sure who "them" was anymore. The counselors at the camp were long gone from his life. His parents couldn't hurt him now. But the fear remained, calcified into instinct: don't let anyone see you angry. Angry boys got sent away. Angry boys got corrected.

He moved on. The study was at the end of the hall.

He saved it for last.

The door had always been locked when he was a child. Grandfather's domain, forbidden and fascinating in the way that forbidden things are to boys. He remembered pressing his ear to the oak once, trying to hear what happened inside. His father had caught him. He hadn't yelled—David Milligan Jr. didn't yell—but had explained, in that quiet voice that was worse than yelling, that some spaces were not for children.

Some spaces are not for you, was what he'd meant. Some spaces were for real Milligans, for men who would grow up to matter.

The door was unlocked now. Everyone who might have stopped him from entering was dead.

Garrett pushed it open.

The study was smaller than he'd built it up to be, all those years of imagining. A desk dominated the center, mahogany, massive, the kind of desk that said its owner made decisions affecting other people's lives. Bookshelves lined the walls, these organized by subject, not color. Law. Finance. History. Biography. A section on Kansas City that took up an entire shelf.

The smell was stronger here. Cigars, definitely. And paper. The kind that yellowed and softened at the edges.

Garrett sat in his grandfather's chair. Leather, cracked with age, molded to a body that wasn't his. He felt wrong in it, like a child trying on his father's suit. Like a trespasser. Like someone pretending to be a person who mattered.

But beneath that familiar feeling—the wrongness, the not-belonging—something else stirred. Something that noticed how the chair felt under him. How the desk spread out like a kingdom. How the whole room seemed to orient itself around this seat, this position, this place of power.

What would it feel like to belong in a chair like this?

The desk had seven drawers. Garrett started with the top right, arbitrarily, without expectation. Papers. Bills. A checkbook with a balance that made his stomach clench—more money sitting in a dead man's account than Garrett had earned in five years of loading docks and warehouse floors and jobs that left him smelling like diesel at the end of every shift.

He closed that drawer carefully. Quietly. The way he did everything.

Second drawer: correspondence. Letters from lawyers, financial advisors, a woman named Helen who seemed to be a housekeeper. Ordinary. Boring. The administrative detritus of a life winding down. Garrett felt a strange disappointment. What had he expected? What had he hoped to find?

Third drawer: photographs. He flipped through them without lingering, but his hands slowed on their own. His father as a young man, grinning in a way Garrett had never seen in life. His aunt, who'd died before Garrett was born, beautiful and unaware of what was coming. Margot at various ages, always polished, always performing for the camera with a smile that never quite reached her eyes.

And then: Garrett. Seven years old, maybe eight. Sitting on a porch somewhere—this porch, he realized, the front porch of this house—with his grandfather standing behind him. The old man's hand was on Garrett's shoulder. Neither of them was smiling, but there was something in the photograph that made Garrett's throat tighten. A connection. A claim.

He didn't remember the day the picture was taken. He didn't remember his grandfather ever touching him with anything like affection.

There were more photos of him underneath. Before the trouble. Before Utah. Before he'd become the family's failed investment. After that summer, the camera had stopped finding him.

He closed the drawer.

The bottom drawer was locked.

Garrett stared at it. Pulled the handle again, harder, as if it might change its mind. It didn't.

Fine. I’ll change it for you.

Garrett pulled out his pocket knife and wedged the blade into the lock. It was old, the mechanism simple. Three minutes and it gave way.

Inside was a leather box. Dark brown, worn smooth at the corners, the kind of thing a man might keep deeds in. Or stock certificates.

Maybe a will?

Garrett shook that thought away. Ridiculous. Grandfather would have had an estate lawyer all picked out. No doubt his will had already been read and Margot knew exactly what portion of the fortune she’d be getting.

He lifted it onto the desk and opened it.

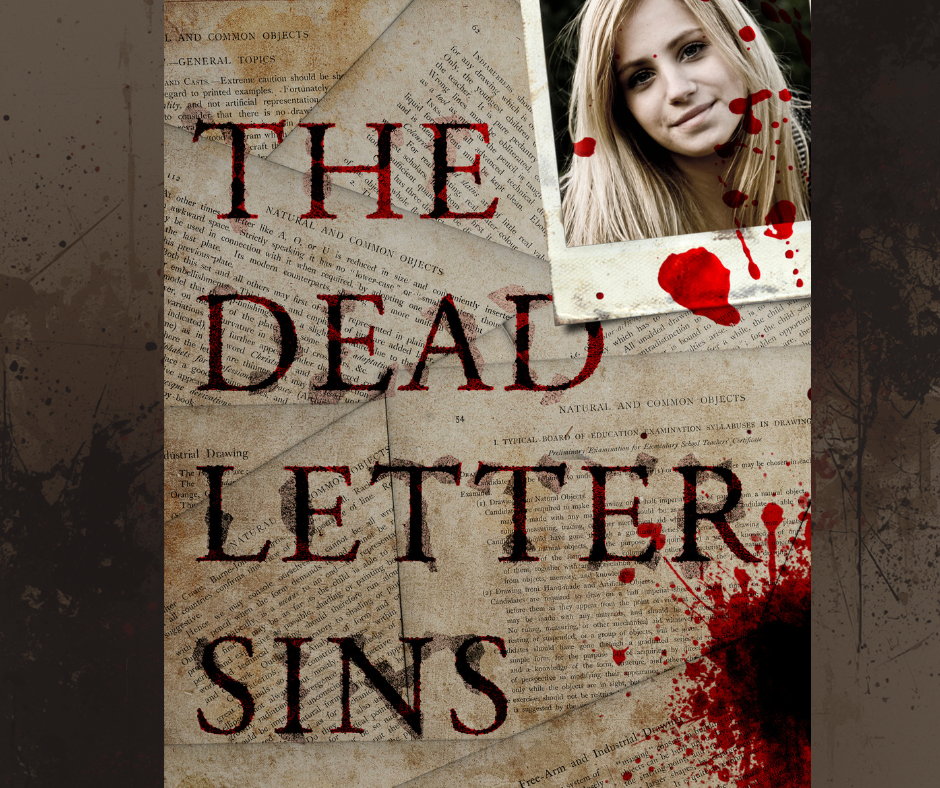

Letters. Dozens of them, maybe hundreds. Handwritten, on heavy cream paper, each one folded and tucked into its own envelope sealed with wax. There were no stamps or addresses. Just names written on the fronts in different hands.

He recognized the first name immediately. Everyone in Kansas City would have. A former mayor, dead now for six years, beloved in the way that dead politicians always were. Garrett remembered the funeral coverage—three days of retrospectives and tearful testimonials, the whole city pretending they'd lost a saint.

He slit the seal with the knife and unfolded the letter.

Dear Hal,

I'm writing this at your request, though I confess I don't understand why you want it in writing. You've kept my confidence for thirty years. I trust you'll keep it for thirty more.

In the summer of 1985, I was involved in an accident on Highway 71 near Richards-Gebaur. I was driving home from a lady friend’s house. I had been drinking—not enough to feel impaired, or so I told myself, but enough. A girl was walking on the shoulder and I swerved to hit her with my car.

It was intentional, and seemed funny at the time.

By the time I got home, I'd convinced myself it hadn't happened. That I'd imagined it, or that it had actually been a deer I’d hit. I didn't watch the news for a week. When I finally did, there was nothing. No body found. No missing person report. I told myself I'd been wrong.

I wasn't wrong.

Three months later, a man came to see me. He said he'd found her. He said he'd taken care of it. He said you'd sent him.

I've never asked you what "taken care of it" meant. I've never wanted to know. I've told myself for forty years that maybe she lived, maybe he just drove her to a hospital, maybe I'm not what I know I am.

I trust your discretion, as always.

The letter was signed with the mayor's full name. His handwriting—Garrett had seen it on proclamations, on framed commendations.

Garrett looked at the box. At the dozens of envelopes still inside, each bearing a name on the front.

A state senator. A federal judge. The man who'd built half the shopping centers in Johnson County. Names that appeared on buildings and foundations and hospital wings. Names that meant something in this city, in this state, in some cases in Washington itself.

What in the holy hell was going on here?

Garrett's hands were shaking. He set down the mayor's letter and reached for another envelope, then stopped. There were too many. He couldn't process this, not here, not sitting in a dead man's chair in a house that had never wanted him.

But one thing was already clear.

Margot knew these letters existed.

And she'd sent her burnout brother—the family failure, the one nobody would believe, the one who could be discredited in an instant if he tried to talk—to find them.

The question was why.