In Defense of Spending Time with Terrible People

Somewhere in the Amazon reviews of almost every novel with a complicated protagonist, you'll find it: "I couldn't root for her." "He was impossible to like." "DNF because I didn't care what happened to these people."

Or the one-star review from someone who powered through the book anyway, furious that the author had wasted their time with a character who wasn't nice.

This is the likability mandate, and it's killing fiction.

"Likable" Doesn't Mean What You Think It Means

Sorry to steal the politician’s favorite stalling phrase, but let me be clear about what we're discussing. The demand for likable protagonists isn't about wanting well-drawn characters, or characters with interiority, or characters whose choices make psychological sense. Those are reasonable expectations. The likability mandate is something else: the insistence that protagonists be good—or at least someone you'd want to get a drink with.

It's the reader saying: I will only spend time with fictional people I approve of.

It’s an extension of a terminal case of main-character syndrome so many people have now: an insistence that every acquaintance, family member, colleague, and even famous movie star, author, or dirt-bag livestreamer reflect the exact morals and opinions of you. The incredible you.

This, by definition, removes the likes of Tom Ripley, charming and hollow, murdering his way across Europe. Humbert Humbert, monstrous and eloquent, making you complicit in his obsession through the seduction of his prose. Amy Dunne, meticulous and vengeful, exposing the rot beneath a marriage while being herself entirely rotten. Ignatius J. Reilly, bombastic and insufferable, raging against a modernity that deserves the raging.

These characters are not likable. They are not meant to be liked. And yet you still see social media screeds (all devoid of capital letters for some reason) decrying Lolita as pedo apologia. It’s not, you dumb bitches. It never was.

These horrible characters are meant to be experienced—to take you somewhere you wouldn't go on your own, to make you feel things you'd rather not feel, to implicate you in perspectives you'd never willingly adopt.

That's what fiction is for.

Fiction Isn't Friendship. Or a Mirror.

The likability mandate misunderstands the transaction between reader and text. It assumes the purpose of a novel is to provide company—pleasant fictional friends to spend a few hours with, characters who reflect your values back at you, who make choices you'd endorse.

But fiction isn't friendship, certainly not the vapid, surface-level version of it the Zoomers and Alphas experience. It’s more like a séance. You're summoning something into the room with you, and the interesting question isn't whether you'd invite it to dinner but whether its presence changes you.

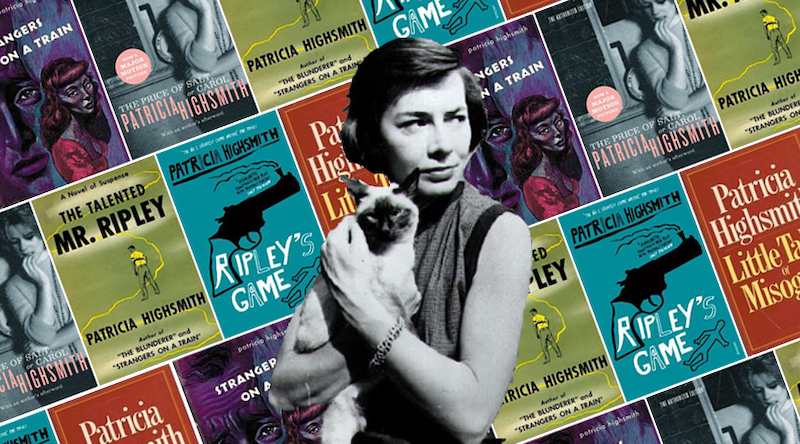

Patricia Highsmith understood this. Her Ripley novels are masterclasses in forcing identification with someone you should despise. Tom Ripley kills people. He lies compulsively. He feels no remorse. And yet Highsmith constructs the narrative so that you're rooting for him to get away with it—not because murder is acceptable but because she's made you inhabit his perspective so completely that his survival becomes your narrative desire.

That's the point. Highsmith is demonstrating something about how identification works, how easily we extend empathy to those whose viewpoint we share, how moral judgment becomes suspended when we're inside someone's head. The discomfort you feel when you catch yourself hoping Ripley escapes is the novel doing its job. It's showing you something about yourself you didn't know.

The reader who DNFs because Ripley isn't likable has refused the lesson.

Unlikeable Females Get it Even Worse

Like I mentioned in last month’s feature article, Gillian Flynn took a lot of heat for Amy Dunne. Gone Girl was a phenomenon, and a certain strain of criticism couldn't forgive Flynn for creating a female villain who wasn't secretly sympathetic, who wasn't the product of trauma that explained her behavior, who was simply—magnificently—awful.

Flynn addressed this in an essay, pointing out that male antiheroes get to be complicated without being excused. We don't demand that Walter White be likable or Hannibal Lecter to have a heart of gold. But a woman who's genuinely terrible seems to require justification (usually a backstory of abuse).

"The one thing that really frustrates me is this idea that women are innately good, innately nurturing," Flynn said. Women are "just as violent and jealous and cruel" as men, and pretending otherwise is its own form of sexism—the soft bigotry of assuming women lack the full range of human capacity, including the capacity for evil.

Amy Dunne is a great character because she's not redeemed. She's not explained. She's not secretly the victim. She's a monster, and the novel asks you to spend time with her anyway, to understand her logic even as you recoil from her actions. The readers who wanted her to be sympathetic wanted a lesser book.

The Real Reason You Won't Read About Bad People

There's a case to be made that the likability mandate is a symptom of broader cultural rot—the same impulse that produces trigger warnings on syllabi and content advisories on classic novels. It's the demand that art be safe, that it not challenge you, that it provide the same dopamine hit as scrolling social media: pleasant, affirming, instantly forgettable.

But I think it's something simpler and uglier. The likability mandate is moral cowardice.

Reading about terrible people makes us uncomfortable because it forces us to recognize that we understand them. We know why Humbert does what he does. We’ve never coveted a child because we’re not sickos in need of a well-oiled wood chipper. But we have, all of us, wanted someone we couldn’t have and who didn’t want us back, and we thought about how it might feel to just… make them.

We feel the logic of Amy's revenge. We comprehend, at some level, the seduction of Ripley's freedom from conscience. This recognition is disturbing. It suggests that the line between us and them is thinner than we'd like.

The reader who refuses unsympathetic protagonists is refusing to know this about themselves. They want fiction that confirms their goodness, that draws a bright line between the reader and the monster, that assures them they'd never be capable of such things. They want flattery disguised as entertainment.

But the best fiction doesn't flatter. It interrogates. It puts you in positions you didn't choose and asks what you find there.

None of this means every protagonist should be a villain. Fiction needs its heroes too—characters who embody what we aspire to, who model courage and decency, who give us something to reach toward. My objection is to the insistence that all protagonists be sympathetic, that fiction's only mode is aspiration.

Sometimes fiction's mode is confrontation, where the valuable thing is not showing you who you want to be but who you might already be, in the dark, if circumstances conspired.

The unsympathetic protagonist is a stress test for your empathy. Can you extend understanding to someone you don't approve of? Can you inhabit a perspective without endorsing it? Can you hold two things at once: recognition and judgment, comprehension and condemnation?

The ability to understand people you find reprehensible is the foundation of everything from criminal justice reform to international diplomacy. You cannot engage with the full range of human behavior if you've only ever practiced empathy with people you like.

The next time you're tempted to put down a book because the protagonist is "unlikable," ask yourself what you're really avoiding. Is the character poorly drawn—unmotivated, inconsistent, a cartoon rather than a person? That's a legitimate complaint. Craft failures are real.

But if the character is vivid and coherent and you simply don't enjoy their company, if you understand them but don't like what you see… consider staying. Consider that the author has taken you somewhere you wouldn't go on your own, and the trip might be worth the unpleasantness.

Fiction is a safe window into other selves, including selves you'd rather not acknowledge. It's one of the things fiction does that nothing else can: force intimacy with the alien, the repugnant, the human.

You don't have to like them. You just have to let them in.