How America punished outcasts who played pretend

In 1994, if you wanted to know who played Dungeons & Dragons at the local high school, you had to earn that information. The guys who met in Tim Fenstermacher’s basement every Saturday didn't advertise. They didn't wear band shirts for games the way metalheads wore Slayer or Megadeth. You found out the same way you found out who was gay or whose dad hit them—through slow trust-building and careful confession. Someone would mention they liked fantasy novels. You'd mention you'd seen the Monster Manual at the bookstore. They'd glance around the cafeteria. If nobody was listening, they might tell you about their half-elf ranger.

Nobody wanted to be the kid who played D&D. The social cost was too high, and in the mid-nineties, the stakes felt existential in a way that's hard to explain to anyone who grew up watching Stranger Things. Those kids were worse than nerds. In the minds of concerned parents and local news anchors, they were potential cultists, possible Satanists, one bad gaming session away from slitting their wrists or murdering their families. The hysteria had mostly died down by the time I was in high school, but its residue coated everything.

Dungeons & Dragons was something to hide.

But if D&D players were whispered about, Vampire: The Masquerade players were mythologized. I didn't know anyone who played Vampire, at least not anyone who'd admit it to me. I just knew they existed somewhere—in cities, probably, or in the bad parts of town. People talked about them the way they talked about swingers or people who went to raves. Freaks who dressed in black, wore fake fangs, drank each other's blood, and held their meetings in cemeteries. The game's very name suggested deception, a double life, something concealed from daylight.

It would take me years to understand what Vampire: The Masquerade actually was, and what it meant to the people who played it. It would take longer to understand what was done to them.

To grasp what happened to Vampire players, you first have to understand what happened to D&D players—because the playbook was written a decade earlier, and the people who wrote it never stopped using it.

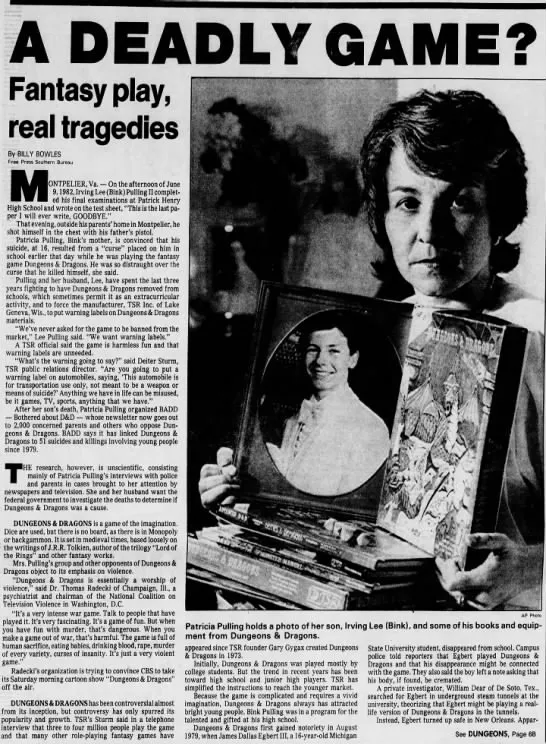

In August 1979, a sixteen-year-old prodigy named James Dallas Egbert III disappeared from Michigan State University. Egbert was brilliant, troubled, and struggling. He had depression, did drugs, and had questions about his sexuality at a time and place that offered no tolerance for it. When he vanished, his family hired a private investigator named William Dear, who knew nothing about Dungeons & Dragons but had heard Egbert played it. Dear theorized, publicly and without evidence, that the boy had gotten lost playing a "live-action" version of the game in the university's steam tunnels.

The media ran with it. Front-page stories speculated that D&D had swallowed this gifted child into a fantasy he couldn't escape. The truth was darker and simpler: Egbert had attempted suicide. He'd hidden in the tunnels to die, failed, and fled campus in shame. He made another attempt with cyanide. He worked on an oil rig in Louisiana. He eventually came home, and a year later, he shot himself.

His parents never blamed the game. But the story was already out there, and the story was more interesting than a depressed kid with a drug problem and no one to talk to about being gay in 1979. Rona Jaffe wrote a novel based on Dear's theory. Tom Hanks starred in the TV movie. A generation of parents learned that D&D could make your children disappear.

Three years later, a woman named Patricia Pulling lost her son Irving to suicide. He was sixteen. He shot himself with his mother's gun, two weeks after losing a student council election at school. Pulling needed an explanation that didn't implicate her own weapon or her son's isolation or the cruelty of high school social hierarchies. She found one: a Dungeons & Dragons game run by his school principal had put a "curse" on Irving's character. The curse, she decided, had driven him to his death.

She sued the principal. She sued TSR, the game's publisher. Both suits were dismissed. But Pulling wasn't finished. She founded Bothered About Dungeons & Dragons—BADD—and dedicated herself to convincing America that a tabletop game was a Satanic recruitment tool. She spoke on 60 Minutes opposite Gary Gygax, D&D's creator. She distributed materials to police departments instructing them on how to interrogate teenagers who played the game. She described D&D as promoting "demonology, witchcraft, voodoo, murder, rape, blasphemy, suicide, assassination, insanity, sex perversion, homosexuality, prostitution, satanic type rituals, gambling, barbarism, cannibalism, sadism, desecration, demon summoning, necromantics, divination."

That's a direct quote.

BADD's methodology was garbage. Of the fifty-plus "D&D-related deaths" Pulling claimed, only a quarter were actual suicides. One was a character in a novel. By 1990, a game designer named Michael Stackpole had systematically dismantled her data in The Pulling Report. The math didn't work: over five years, roughly twenty-eight adolescents who played D&D committed murder or suicide. By 1984, three million American teenagers were playing the game. The baseline adolescent suicide rate was around 360 per year. D&D players were statistically less likely to kill themselves than their non-playing peers.

The CDC, the American Association of Suicidology, and Health and Welfare Canada all concluded by 1991 that there was no causal link between role-playing games and suicide. Patricia Pulling died of cancer in 1997, and BADD died with her. But she'd accomplished something real: she'd given grieving parents a framework to turn self-blame into righteous fury, and she'd given the media a story too lurid to fact-check. The ground was salted. When the next wave of outcasts found their game, they'd walk into a trap already laid.

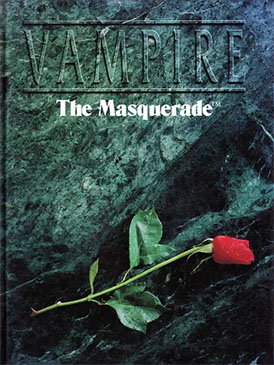

Vampire: The Masquerade arrived in 1991, and it was designed for kids who didn't want to be heroes.

Mark Rein-Hagen's game was set in a "gothic-punk" version of the modern world—darker, dirtier, more corrupt than our own. Players took on the role of vampires, but not the romantic Anne Rice kind or the monstrous Nosferatu kind. These vampires were both. They were people who'd been transformed into predators and now struggled against their own bestial natures, against vampire hunters, against each other, and against an elaborate secret society of undead politics. They called themselves "Kindred." They organized into clans with names like Toreador and Ventrue and Malkavian. They operated under a law called the Masquerade: never let the humans know what you are.

The game attracted a different crowd than D&D. Where D&D drew kids who wanted to be Conan or Gandalf, Vampire drew kids who already felt like monsters—goths, theater kids, outcasts who'd been primed by Anne Rice novels and Sisters of Mercy albums to find beauty in darkness. In 1993, White Wolf published Mind's Eye Theatre, a live-action version that used rock-paper-scissors instead of dice. Suddenly you could play Vampire in public. You could dress up. You could go to goth clubs and cemeteries and parks and run your elaborate social intrigues with dozens of other players.

This was unprecedented. D&D players had stayed in basements, invisible to the world. Vampire players were visible. They wore black clothes, pale makeup, fake fangs. They developed their own slang. You weren't just turned into a vampire, you were "Embraced"; your creator was your "Sire"; you weren't a vampire at all, you were "Kindred." They had tribal markers, a vocabulary, a look. And for kids who'd never found a tribe, who'd never fit anywhere, who'd been told their entire lives that something was wrong with them, Vampire offered something precious: a community where being strange was the whole point.

The game's central rule was "don't break the Masquerade"—don't let mortals see what you really are. Unfortunately, that rule would be broken in the worst way possible.

On November 25, 1996, a married couple named Richard Wendorf and Naoma Ruth Queen were bludgeoned to death in their home in Eustis, Florida. The murderers were teenagers. The mastermind was a sixteen-year-old named Rod Ferrell.

Ferrell's backstory was a horror story. He'd allegedly been sexually abused by his grandfather at age five. His mother, Sondra Gibson, worked as an exotic dancer and sex worker; she later pled guilty to soliciting sexual favors from a fourteen-year-old boy. By his mid-teens, Ferrell was addicted to multiple drugs, including PCP, LSD, and heroin. He'd been diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder. In October 1996, he broke into an animal shelter and killed two puppies.

He also claimed to be a five-hundred-year-old vampire named "Vesago."

What Rod Ferrell was, by any clinical or legal definition, was a deeply disturbed child who had been failed catastrophically by every adult in his life. What the media called him was "the leader of a vampire cult."

Ferrell had traveled from Kentucky to Florida with three accomplices to pick up a friend, Heather Wendorf, who wanted to run away from home. He and a friend broke into Heather's house, beat her parents to death with a crowbar, and burned a V-shaped mark into her father's body. They fled to Louisiana and were arrested on Thanksgiving Day after one accomplice called a relative.

The media coverage was overwhelming. "Vampire Cult Killings" dominated headlines. Local news dug up every detail about Ferrell's interest in Vampire: The Masquerade, his use of the game's terminology, his alleged blood-drinking rituals at an abandoned building in the Kentucky woods that teenagers called "the Vampire Hotel." A local LARP group called VAMPS—Victorian Age Masquerade Performance Society—scrambled to distance themselves from the murders. "People are always going to find a scapegoat," their leader told reporters, "and I don't want VAMPS to be that."

They found their scapegoat anyway. Ferrell became the youngest person on death row in the United States. His sentence was later reduced to life without parole. The other accomplices received sentences ranging from ten to seventeen years. Heather Wendorf was cleared of all charges. But the damage was done: Vampire: The Masquerade was now, in the public imagination, the game that made teenagers kill.

Five years later, on the other side of the world, a student named Aline Silveira Soares was found dead in a cemetery in Ouro Preto, Brazil. She'd been stabbed seventeen times.

Prosecutors blamed Vampire: The Masquerade. They claimed that Soares had "lost" an RPG game and had been ritually executed according to "Satanic precepts." A supplemental book called The Book of Nod—a collection of fictional poetry about vampire mythology—was displayed on Brazilian national television as a "Satanic bible." Vampire: The Masquerade was temporarily banned by the Brazilian justice system.

Three residents of the student house where Soares had been staying were charged with her murder. For years, the Brazilian Vampire community faced persecution and stigma. The media treated the case as proof that the game was dangerous.

In July 2009, after an eight-year ordeal, all three defendants were acquitted.

A Brazilian legal scholar named Cynthia Semíramis Machado Vianna later wrote that "the press promoted a campaign of disinformation, establishing a nonexistent relationship between RPGs with what authorities supposed to be black magic and satanic rituals." The media, she argued, "should have respected the intelligence of the public." Instead, "RPG games and players were misrepresented for years, instilling condemnation and persecution." After the acquittals, the same media outlets that had convicted the game in the court of public opinion suddenly questioned the investigation.

The defendants were exonerated. The stigma remained.

Here is the thing that no one wanted to reckon with, not in 1979, not in 1996, not ever: the kids who found these games were already struggling.

They were isolated. They were bullied. They were weird in ways their parents couldn't fix and their schools refused to accommodate. Some of them came from homes with abuse or addiction or neglect. Some of them were queer in places that punished queerness. Some of them were just different, and different was enough.

Role-playing games gave them something real, a community. They gave them a space to try on identities, to work through feelings, to belong to something. The research couldn’t be more clear: social connection protects teenagers from suicide, and role-playing games provide social connection. If anything, the games were helping.

But that wasn't the story America wanted to tell. The alternative explanation—that these kids were damaged before they ever picked up a rulebook, that the adults in their lives had failed them, that we had failed them—was unbearable. If the problem was abuse or mental illness or homophobia or parental negligence, then we'd have to do something about abuse and mental illness and homophobia and parental negligence. If the problem was a game, we could just ban the game.

Patricia Pulling didn't want to believe she'd left a gun where a suicidal teenager could find it. Rod Ferrell's mother didn't want to believe she'd raised her son in chaos and predation. The parents of every kid who ever hurt themselves didn't want to believe they'd missed the signs. Of course they didn't. That's an impossible weight to carry. Grief does terrible things to people, and the need to find a villain outside yourself is one of them.

What BADD did—what the media did—was take that grief and weaponize it. They told grieving parents that their guilt was misplaced, that the real villain was a box of dice and a book of monsters. They offered absolution at the price of someone else's scapegoating. They created a framework where the most vulnerable kids in America could be twice punished: once for being outcasts in the first place, and again for finding the only communities that would have them.

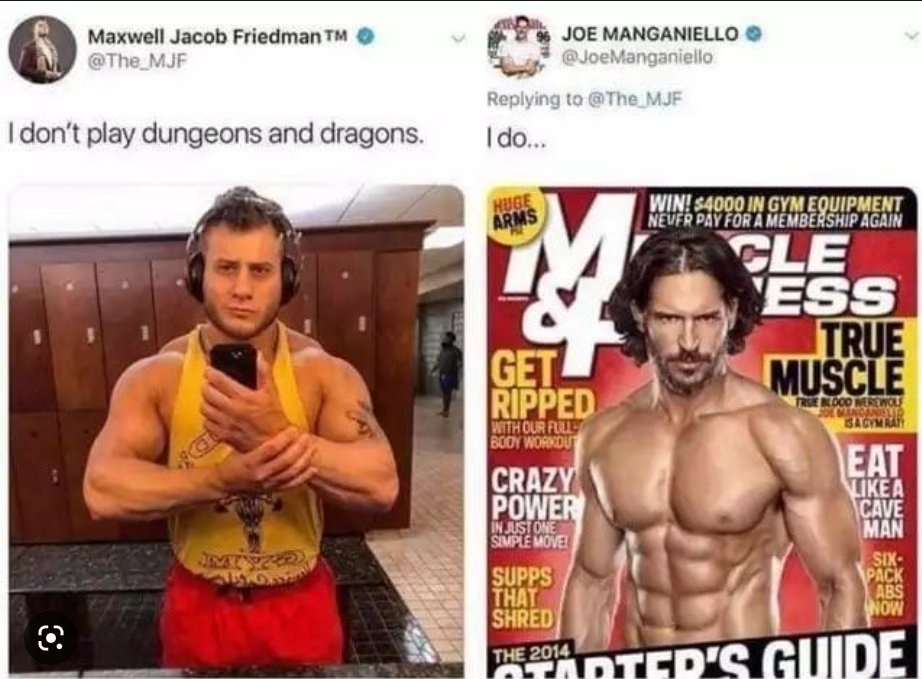

Dungeons & Dragons is cool now. Stranger Things made it cool. Critical Role made it cool. Joe Manganiello and Vin Diesel made it cool. The game that parents once burned in their backyards is now a $150 million blockbuster franchise. Forty percent of its players are women. D&D clubs meet in middle schools. Nobody blinks.

Vampire: The Masquerade still exists. It's on its fifth edition. Bloodlines 2, the sequel to a cult-classic video game, has been in development for years. There are still LARPs that meet in cities around the world, still players who gather to scheme and betray each other in the language of Kindred and Clans.

But the stigma never fully lifted. D&D got rehabilitated because it could be framed as wholesome—kids sitting around a table, rolling dice, fighting dragons. Vampire's aesthetic was always darker, always more adult, always more tied to goth culture and nightlife and, yes, sometimes to sex. The LARP scene, in particular, had a reputation. Some of it was earned—there were games where the social dynamics got unhealthy, where the line between character and player blurred in damaging ways. Most of it was tabloid fantasy. But the reputation stuck.

I talked to a woman recently who played Vampire in the nineties. She's in her fifties now, a professional, a parent. She still doesn't tell people about it. "D&D is something you can put on a dating profile," she said. "Vampire is still something you explain."

The kids who needed Vampire the most—the ones who felt like monsters, the ones who found beauty in darkness, the ones who built their first real friendships around a table in a goth club—many of them are middle-aged now. They carry the memory of what it cost to be visible, and what it cost when visibility made them targets. They remember the news coverage, the accusations, the parents who wouldn't let their children come over, the way a game they loved became synonymous with murder and Satanism and everything wrong with American youth.

Some of them still play. They play with their kids, or they find new groups online, or they host small games in their living rooms with friends who understand the history. The newer editions have changed some things. There's less edge, less danger, more awareness of how games can go wrong. It's been sanitized, a little, for a generation that didn't live through the panic.

Maybe that's fine. Maybe every community has to sand off its roughest edges to survive. Maybe the kids who find Vampire now don't need it to be as dark as it was, because they're growing up in a world where being different isn't quite the crime it used to be.

Or maybe they do. Maybe there are still kids out there who feel like monsters, who don't fit anywhere, who need a community that understands what it's like to be cast out. Maybe they'll find Vampire, or something like it, and it will save them the way it saved the kids who came before.

And maybe, this time, we'll let them have it.